Lessons Learned From Daily Algorithm Practice

In June I made a goal to study algorithms by solving 1 practice problem each day. I started by using HackerRank. Now about 3 months later, I can say I have learned a lot.

Below are some lessons I learned from around 90 days of daily practice:

Look for shortcuts to avoid loops

Loops are so common in software development that we probably don’t give them much thought. If a problem requires doing something with multiple pieces of data, the simplest approach usually involves using a loop to operate on each piece in turn.

While simple looping works for small sets of data, it can be painfully slow when working with large sets. Fortunately, some problems that seem to require a loop-based solution actually don’t require loops at all! If you notice certain patterns in the problem, there may be a way to cheat instead.

Cheat with math

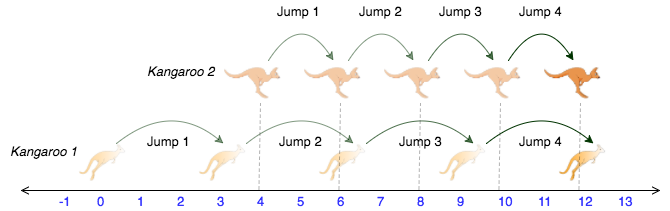

If a problem has a pattern that feels like math, there may be a formula-based solution. Here’s one such problem on HackerRank: Number Line Jumps. Given two kangaroos jumping in the same direction, identify whether they will ever meet at the same point given their starting positions and speed.

In my ignorance I muddled my way through it by checking for an edge case and then looping an arbitrarily high number of times to try to brute force all the test cases:

public static string kangaroo(int x1, int v1, int x2, int v2)

{

if (v2 != v1){

var fasterKangaStartsAhead = v2 > v1 ? x2 > x1 : x1 > x2;

if (fasterKangaStartsAhead) return "NO";

}

for (var j = 0; j <= 10000; j++){

if (x1 + j * v1 == x2 + j * v2){

return "YES";

}

}

return "NO";

}It worked, but far better would have been to recognize that this is actually a relatively simple algebra problem and so can be solved with a formula, as multiple users in the discussion page pointed out:

public static string kangaroo(int x1, int v1, int x2, int v2)

{

return (x2 - x1) * (v2 - v1) < 0 && (x2 - x1) % (v2 - v1) == 0 ?

"YES" :

"NO";

}After seeing how much faster and shorter a formula-based solution can be, I now always try to look for one before resorting to brute-force loops.

Cheat with logic

Sometimes you can find a math-based pattern in a problem that indicates that it’s possible to solve the problem with a formula. Other times a problem might not have any mathematical patterns, but by stepping back and reasoning about the problem, constraints may emerge that point to a simple solution.

One problem like this on HackerRank is Happy Ladybugs. Given an array of spaces representing a game board filled with ladybugs of various colors, identify whether the ladybugs can be rearranged such that all ladybugs are adjacent to at least one other ladybug of the same color.

At first glance it might look like some type of recursive loop is required to check whether the ladybugs can be sorted correctly. However after thinking about the problem for a bit I realized that only one loop is needed since any ladybug can be moved to any open space, so as long as one of the following is true, the ladybugs can be rearranged correctly:

- The ladybugs are not already arranged correctly, there are no lone ladybugs of a color, and there’s at least one open space, OR

- The ladybugs are already arranged correctly

Below was my solution:

public static string happyLadybugs(string b)

{

var spaceDict = new Dictionary<char,int>();

var boardStack = new Stack<char>(b);

var loners = 0;

var lastSpace = '\0';

while (boardStack.Count > 0){

var space = boardStack.Pop();

if (spaceDict.ContainsKey(space)){

spaceDict[space]++;

}

else {

spaceDict.Add(space, 1);

}

if (boardStack.Count > 1){

if (space != lastSpace && space != boardStack.Peek()){

loners++;

}

lastSpace = space;

}

}

if (spaceDict.Any(x => x.Key != '_' && x.Value == 1)

|| (!spaceDict.ContainsKey('_') && loners > 0)){

return "NO";

}

return "YES";

}Early on I was dumbfounded how others seemed to be able to see opportunities for shortcuts like these, but over time as I practiced I started to learn what to check for and ways to “cheat” started to become more obvious.

Look for opportunities to use a stack

Apart from learning to look for shortcuts to avoid loops, another trick I picked up on is that when loops are required, look for opportunities to simplify them by using a stack. A simple example is identifying unique combinations of elements in a set.

One way to find unique combinations of two elements in a set could be to use nested for loops like this:

public static List<int[]> findCombinations(int[] array)

{

var combos = new List<int[]>();

for (var i = 0; i < array.Length; i++){

for (var j = i+1; j < array.Length; j++){

combos.Add(new [] { array[i], array[j] });

}

}

return combos;

}However I found that it’s simpler to implement the above using a stack instead since you don’t have to fuss with indices, even though it takes an extra line or two:

public static List<int[]> findCombinations(int[] array)

{

var combos = new List<int[]>();

var stack = new Stack<int>(array);

while (stack.Count > 1) {

var top = stack.Pop();

foreach (var element in stack) {

combos.Add(new [] { top, element });

}

}

return combos;

}One gotcha though is that when initializing a stack using a collection, the elements in the stack will be in reverse order (at least in C#). In the example above it doesn’t matter, but it’s something to be aware of for when order does matter.

Recognize when there is no shortcut

Finally, despite sometimes being able to find shortcuts or tricks to simplify a solution, there are times where the only option is brute force. For example, one HackerRank problem (ACM ICPC Team) requires identifying combinations of known subjects among attendees of a programming contest. In this case there is no secret solution, you simply have to loop over all attendees and build all possible combinations.

The lesson here is while it’s useful to know how to find shortcuts, it’s equally useful to know how to tell when there is no shortcut so that you can get on with solving the problem without wasting time.