My .NET Core Unit Test Strategy

Unit testing is a critical part of modern software development. Unit tests enable a codebase to evolve and grow by making sure new changes don’t break existing functionality. Without unit tests, the quality of a codebase quickly degrades because as the functionality grows, the likelihood that a human can manually test it all decreases.

Here’s how I approach unit testing in .NET Core:

Contents

Project structure

To begin, here’s an outline of how I prefer to structure my unit test projects:

- Unit Test Project

- A folder for the type of component being tested (e.g. “Services”)

- A folder for each component concern (e.g. “FileStorage”, “Authentication”)

- A file for each public method on the component class (e.g. for FileStorage: “TheSaveMethod.cs”, “TheLoadMethod.cs”)*

- A file named “Init.cs” to hold set up functionality that’s shared by the method files

- A folder for each component concern (e.g. “FileStorage”, “Authentication”)

- A folder for the type of component being tested (e.g. “Services”)

*I prefer to have separate files for each method instead of just one file for all tests because there could be a lot of tests for each method.

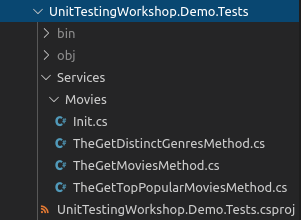

Here’s an example unit test project from a demo I presented:

These tests are for a MovieService that has three public methods: GetMovies, GetTopPopularMovies, and GetDistinctGenres. The Init.cs file contains a static method that provides a common set of dummy movie data for the tests.

Tools

Testing framework: xUnit

The testing framework handles organizing and running the tests. I prefer to use xUnit because its syntax feels more intuitive to me than MSTest’s or NUnit’s. All I have to do is add a [Fact] attribute to my test methods.

Mocking library: Moq

A mocking library helps provide fake implementations of any dependencies of the component being tested. Using fake implementations of dependencies is necessary to ensure that each test is only testing the intended component. If real dependencies are used in testing, then the test is no longer a unit test, but an integration test.

So far I’ve used Moq because it seems to be the most popular mocking library, but NSubstitute is also attractive because of its simpler syntax.

Writing

Here’s an example of a unit test for the GetMovies method of the MovieService:

public partial class MovieServiceTests

{

public partial class MovieServiceTests

{

public class TheGetMoviesMethod

{

[Fact]

public void ShouldGetMovies()

{

var mockMovieDataService = new Mock<IMovieDataService>();

mockMovieDataService.Setup(s => s.LoadMovies())

.Returns(CreateTestMovieCollection());

var movieService = new MovieService(mockMovieDataService.Object);

var movies = movieService.GetMovies();

Assert.Equal(5, movies.Count());

}

}

}

}The ShouldGetMovies method is decorated with xUnit’s [Fact] attribute, which tells xUnit that this is a test method. The MovieService depends on an IMovieDataService, so a mock data service is created using Moq. The mock data service’s LoadMovies method is set up to return the test data defined in Init.cs instead of real data.

Running

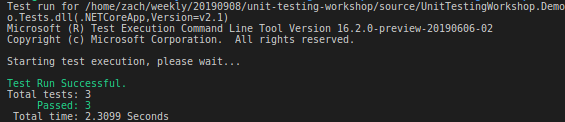

Running xUnit tests in .NET core is super easy. In Visual Studio, the Test Explorer window automatically detects any xUnit tests in the solution. On the command line, simply navigate to the test project’s directory and run dotnet test. Either approach will indicate which tests passed or failed:

Conclusion

This has been a high-level overview of how I currently structure, write, and run unit tests using xUnit and Moq in .NET Core.